The blog is back!

I know it has been a while, and it feels good to be writing and exploring herbs with you all again. I thought I would start off with some quick’n’easy, LOW-ENERGY foraging pointers to get you geared up for what I’m sure will be another busy summer. If you’re like me, you started garden plans in January and are juggling 40 different projects at once in the name of “ALMOST SUMMER”, so you might find it difficult to go on your usual foraging ventures. Here are four quick plants that you might not even have to leave your neighborhood to enjoy!

Dandelion

(Taraxacum officinale)

Let’s start with the most obvious low-energy foraging plant out there: The dandelion. We have all heard people berate this plant as a noxious weed, but it may surprise the layman to find that the dandelion has dozens of amazing properties that are GOOD for you! From culinary to medicinal to amending soil to getting you to kick that caffeine, dandelion is an undercover super plant! On top of that, it is widely available as it grows all over the world and just about anywhere (even in places you might not want it).

How to Identify:

The mature plant leaves grow in a basal rosette (where the leaves radiate out from the base of the stem and usually close to the ground) connected to a big, white taproot with thin brown skin. The leaves are a deep to bright green and the edges have widely spaced “teeth” that are deeply notched. It tends to have a distinctive rib on the back. Every part of the dandelion will emit a milky, sticky sap when broken.

The flowers are bright yellow and grow singularly at the ends of hollow, leafless stems. They are soft and laden with pollen. Once gone to seed, they turn into what we know as a “puffball” of white seeds, which we usually blow off for wishes.

Foraging:

There is a key factor to really think about when harvesting dandelions. The main element is that it’s probably the most sprayed “weed” out there, so finding a place that is safe for foraging is very important. If it’s your own lawn or away from society/traffic, chances are good for picking these flowers. Another point: do your research on how to identify look-alikes.

Peak dandelion season is usually in the spring, but this plant can grow all season long depending on where you live. Spring foraging comes in delightfully numerous ways. The first thing I like to do before all the blooms have formed is harvest the “dandelion capers” for pickling. Early on, dandelions produce small, pea sized flower buds and, when picked at the right time, are perfect for making what I call Poor Man’s Capers. The key here is to look for them at the very center of the leaf rosette – you may have to push all the leaves out of the way, as these are not readily visible. Sometimes they are in tight clusters. Make sure that they have no stem beneath them and haven’t opened up at all, otherwise you will end up with a pickled ball of petals. You do have to get onto the ground to do this kind of foraging and will usually look like a complete loon to your neighbors, but I assure you that it’s worth it. As the local loon, I collect the capers over the span of a few days and, once I have enough, I pickle them.

That didn’t sound like easy-going foraging though, did it? The flowers are MUCH more convenient. Whether it’s making mead or jams or teas, harvesting the dandelion flowers after they’ve fully opened is easier than pie. Processing them is a little harder, as for some recipes you will want to part the petals from their bracts (or just any green parts). It’s much easier to process them before they wilt, which happens fairly quick after harvesting.

Dandelion leaves are just as easy to forage. Just pluck the smaller, tender ones and go. These are great on salads, in pesto or simply sauteed. The bigger ones are more bitter.

Dandelion root is a bit more difficult. The roots should be harvested in fall, and since the taproot can go very deep into the ground and is too soft to just yank up, you will have to do some digging. Once you harvest it, it can be roasted or added in bitter tinctures right away, or dehydrated for later use. The root is often used alongside chicory as a coffee alternative.

Recipes/Ideas:

2. Cottonwood

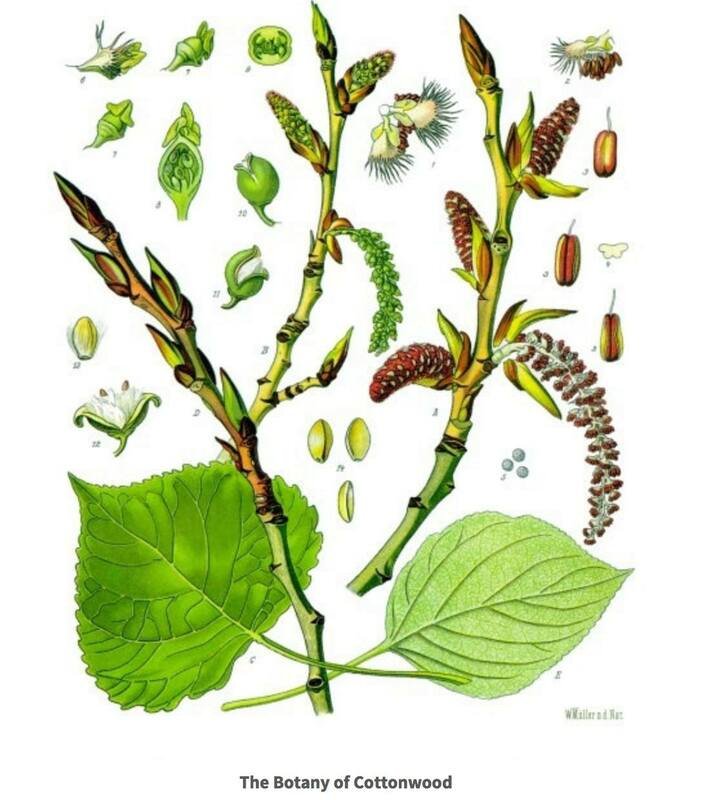

(Populus deltoides, populus balsamifera and populus fremontii)

I’m about to bestow on you the easiest form of foraging you can come across: Cottonwood bud hunting.

One of my favorite trees and probably one that you’ve seen in parks or along riversides, the cottonwood stands as one of the more popular trees to plant because of how quickly it grows. A cottonwood can shoot up 6-12 feet a year and reach 100 feet easily! They are also historically known as an indicator of water, as they prefer to grow in riparian zones – so if you’re in the desert and you see one, you may be in luck!

Ever wonder what that cotton is floating on the wind every fall? Well… look no further. On top of being a really cool tree, cottonwood is harvested for many medicinal uses, mostly for its pain-killing effects. Here you can find out just how low-energy this foraging field trip can be!

How to Identify:

This tree is found all over the United States and has 3 main varieties: pop. deltoides (native to Eastern US), pop. balsamifera (found west of the Rockies and north/south as far as they can go) and pop. fremontii (from California to Utah and Arizona and down into northwest Mexico).

In my opinion, the quickest way to start identifying a cottonwood is by the bark: The younger branches at the top will have smooth, pale bark that might even remind you of aspen. But as you follow down the tree, the older bark becomes darker, rougher and deeply furrowed.

The leaves are typically a broad, triangular shape and have a flat stem. They begin as a vibrant green and eventually turn to a beautiful yellow/gold come autumn. In spring, cottonwoods develop thick, resinous leaf bunds that resemble caterpillar cocoons with a sharp tip and expel a red, sticky sap. They alternate along the thinner limbs and can help you identify this tree even when there are no leaves!

Catkins form in spring as well, which are the flowers of the tree and look like floral versions of cat tails. The female cottonwoods produce cotton in early summer and this contains the seeds that they then spread via the wind – and what is most likely a culprit for your spring allergies!

Foraging:

The parts of the cottonwood tree that we’re mainly focusing on today are the buds. You may have heard of The Balm of Gilead, a treatment developed from harvesting cottonwood buds for the salicin in them, which can reduce pain and inflammation and lower fevers. It’s also a natural remedy for swelling, predominantly in arthritic joints.

The best part is that gathering these buds comes with very little effort on your part and very little harm to the tree. All you have to do is wait for a windy day and you will find that the wind knocks the somewhat brittle branches off the tree, sending a whole harvest worthy amount of buds right into your reach. Just wander down a river path and collect them in a bag. From there, you separate the good buds from potentially rotten ones or any that contain catkins, as they are less resinous.

The leaves of this tree can be harvested in spring and summer and can be used in herbal baths. The bark is boiled as a decoction for fighting infections like coughs or colds. Like roots with other herbs, most nutrients the tree has going inward happens in fall, and it goes into the bark then. Try to harvest from recently fallen limbs rather than from the living tree to protect the longevity of your plant friend. The catkins are rich in vitamins and can be plucked from branches and eaten raw or added to recipes.

WARNING: There can be adverse effects in people who have allergies to aspirin or bee stings.

Recipes/Ideas:

3. Curly Dock and Broad-Leaved Dock

(Rumex crispus and Rumex obtusifolius)

You have probably walked by this plant a dozen times and didn’t think twice about it. Time to take a closer look! Curly dock, also known as yellow dock for its yellow roots, is a versatile, prolific plant of which all the parts are edible: Roots, leaves and stems! Like most amazing, medicinal worts, this plant isn’t exactly picky about its environment, growing in sunny places along roadsides, trail sides, fields and even in your yard! While it was once native to Europe, it has since been introduced to all fifty states in the US.

How to identify:

Young dock grows as a basal rosette at the top of the root, radiating out with long, oval-shaped leaves that are hairless and smooth. These leaves alternate once a stem begins to grow in the second year. Curly dock leaves are very distinct with their wrinkled, curling edges – hence its common name! All of these leaves can grow up to a foot in length while the entire plant can reach almost five feet. Most importantly, dock has a translucent, sometimes slippery “sheath” known as an ocrea at the base of each leaf stem and can become brown and paper over time.

After the first year, dock will send up a thick stock for its unassuming flowers. It may have thin red stripes up the skin. It isn’t ramrod straight, either, and tends to have a wavy bend in it, much like its leaves. In fall, seeds appear on the tall stalk, which has turned a rusty brown.

Foraging:

While this plant can be harvested year-round for different needs, the first round of gathering comes in early spring to early summer, which means you’ll be foraging the leaves. After identifying the correct species, you will want to pick the leaves when they are young, sweet and tender. They can be eaten raw or cooked and have a similar flavor to spinach but with a lemony twist.

The stem should be popping out come late spring and early summer, and you’ll want to catch it before any flowers appear! It should feel bendy and supple, like young asparagus. This can also be eaten raw, but if the stringy outside has developed enough, it can be peeled and then steamed or sauteed.

Seed foraging will happen in late summer after the dock has bloomed and then gone to seed. The seeds will have become rusty brown, dry and papery, and grow in massive quantity. Just strip the seeds from the stem to harvest them. While admittedly hard to process correctly to get the seed away from the chaff, if you’re willing to grind it all together with no issue, dock seeds are worth harvesting to make flour!

The best time to harvest roots is in the fall, while the plant is focusing all its nutrients beneath the ground so it can survive the winter. Before the ground freezes and once you’ve had a cold snap is the best time. For dock, you want to harvest it when the plant has grown to a substantial size, best identified in the second year by the production of its stem and flowers. These roots can be impressively large, so it’s best to use a trowel to dig down around the root rather than yank it up and risk snapping it off in the ground. This part of the plant is not exactly tasty, but it is absolutely used medicinally for constipation, homemade bitters, and soothing irritable bowels.

Recipes/Ideas:

Pickled dock stems (just choose your favorite pickling ingredients and pickle it like asparagus)

Dock flour (just grind seeds and husks into flour. I recommend adding other flours to it, as dock doesn’t contain gluten)

Add dock root to any bitter astringent

4. Plantain

(Plantago major and Plantago lanceolata)

Yet another plant so common, you can’t believe you haven’t added it to your herb arsenal before! Like dock, plantain grows along roads, in disturbed areas and in yards with a keen comfort in either sun or shade. I’m sure you’ve heard this plant called a weed before, despite that it has a very long history as a medicinal wort! Some call it “nature’s bandaid”, as it can be applied directly to bug bites, cuts and bruises. On top of that, the leaves and seeds are edible.

How to Identify:

Growing in a basal rosette, plantain stays low to the ground, with parallel running veins on its bright green leaves - which is why it’s other common name is ribwort. They can be shaped ovular or elongated, depending on the type (broadleaf plantain will be… broad. Narrow leaf will be... narrow). Once ready, it produces a leafless flower spike at the center, which is covered with small, translucent petals. These thin stalks can grow up to 20 inches tall and have white stamens.

Foraging:

The young leaves are edible and should be harvested early in the season while still tender. They are full of nutrients and taste surprisingly of mushroom. If harvested too late, the leaves become tough and stringy, but still have medicinal use and can by dehydrated or used fresh. Plantain is antimicrobial, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory, which is why it’s a popular plant for herbalists and outdoors-folks. Made into a poultice, it can be applied to a series of minor injuries or turned into a handy salve.

The seeds are a little more difficult to just grab and go but can be a lovely addition to salads or ground into flower. Then again, isn’t this blog supposed to be about EASY foraging?

Fun Fact: Did you know that the husks from the plantain seeds are called psyllium husks and can be found in powdered versions at health food stores?

The plantain root has almost the exact medicinal uses as the leaves, so unless you want to go digging roots up in the fall, take advantage of the “easy pickins” of plantain leaves this spring!